By: Rachelle Nuss, MD, FAAP

Sickle cell disease is a group of inherited blood disorders that can cause episodes of severe pain and many other medical challenges. The condition is most often discovered during routine newborn screening tests. Children of all ethnic backgrounds may be diagnosed with sickle cell disease.

Learn more about sickle cell disease and how early and ongoing care and treatment helps manage symptoms and prevent complications.

How does sickle cell disease affect children?

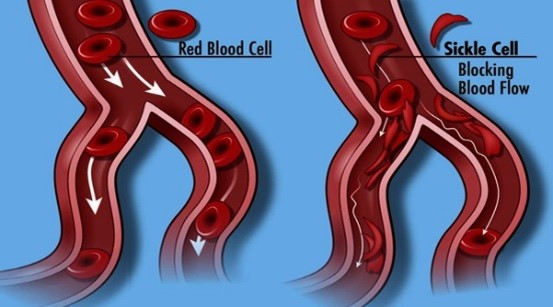

In children with sickle cell disease, a protein called hemoglobin that carries oxygen inside the red blood cells forms chains that clump together. This causes the red blood cell to be shaped like a crescent moon or a sickle tool.

Compared to normal red blood cells that are disk-shaped and flexible, sickled cells are stiff, sticky and fragile. They break apart more easily than normal red blood cells, stick together and damage the blood vessels. This results in areas of blocked blood flow, inflammation (swelling) and less oxygen getting to tissues in the body.

Image Source: U.S. National Library of Medicine

How do infants and children get sickle cell disease?

Babies are born with sickle cell disease. The baby receives one hemoglobin gene from each parent. The "normal" common hemoglobin gene is A. So, most people receive an A from one parent and an A from the other. They are called AA.

But hemoglobin genes may mutate (change) from A to many other types with different letters. The most common change results in S (sickle) or C hemoglobin. The mutated (changed) hemoglobin gene associated with sickle cell disease is S. When an S is joined by some other mutated hemoglobin genes, that combination causes sickle cell disease.

The most common type of sickle cell disease is SS. Another less common type is SC. Sometimes a S is joined with a gene that doesn’t make any A hemoglobin (Sbeta zero thalassemia) or a gene that makes very little A hemoglobin (Sbeta+thalassemia) and that results in sickle cell disease. There are even more. less frequently occurring types of sickle cell disease.

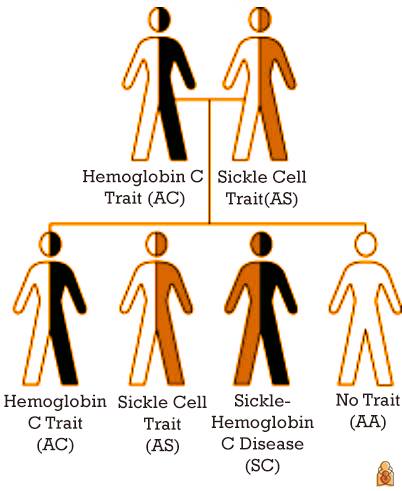

How sickle cell disease is inherited: an example

Genes come in pairs—one from each parent. Which gene a child inherits is random, like throwing a dice. Inheriting one normal A and a mutated or abnormal gene gives someone a "trait."

In the image above, the parents have AC and AS traits, respectively. One of their children inherits the AC trait and one the AS trait. The parents and children are generally well. Often, they may not even know they have a trait.

Inheriting an S, sickle gene, and another abnormal hemoglobin gene may cause sickle cell disease. In the picture above, one child has sickle cell disease, the child who inherits SC. One child inherits the normal or usual pattern of AA.

Image source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

How do I know if my baby has sickle cell trait or disease?

Every state in the U.S. performs a

newborn screening test for sickle cell disease. Your baby’s primary health care provider receives the result and reviews it with you. If a trait is present, the primary caregiver will talk with you about it. If the results suggest sickle cell disease, the baby is referred to a pediatric hematologist (blood specialist for children).

Prompt diagnosis—before infants show any symptoms—allows infants with sickle cell disease to get early treatment and parents to learn about ways to help lower the risk of serious health problems.

Who is affected by sickle cell disease?

A carrier of a single hemoglobin S gene is said to have sickle cell trait or hemoglobin S trait. People with hemoglobin S trait alone do not have sickle cell disease. However, if their reproductive partner also has the hemoglobin S trait, then together they have a 1 in 4 chance (25%) of having a child with sickle cell disease.

About

1 in 12 people of African ancestry carry S trait. About

1 in 365 Black or African American people are born with sickle cell disease each year in the United States.

However, sickle cell trait is also common in people with ancestors from the Caribbean, Middle East, India, South America, Central America and Mediterranean countries such as Turkey, Greece and Italy. Sickle cell trait is found today in descendants of the populations no matter where they live.

Why is sickle cell disease sometimes called sickle cell anemia?

Sickle cell disease is an umbrella term for the many specific types of sickle cell disorders.

Anemia―meaning a lower-than-normal hemoglobin in red blood cells―happens with all forms of sickle cell disease. While normal red blood cells can live for 120 days, sickled cells last only 7 to 20 days; the body can't replace them fast enough resulting in anemia.

Sickle cell anemia refers to the two most severe forms of sickle cell disease, hemoglobin SS and sickle beta zero thalassemia.

Main Types of Sickle Cell Disorders |

Hemoglobin SS | The most severe form, affecting 65% of children with sickle cell disease. Most or all of the hemoglobin is abnormal, causing chronic anemia. |

Hemoglobin SC disease | About 25% of children with sickle cell disease have this mild to moderate form of the disease. Symptoms generally develop later in childhood, but may be as severe as in SS. |

Sickle beta plus thalassemia | Affects around 8% of children with sickle cell disease. This is generally a milder form of sickle cell disease, but severity can vary greatly. |

Sickle beta zero thalassemia | A severe but less common form, accounting for 2% of sickle cell disease. It is similar to hemoglobin SS.

|

Why are infants and children with sickle cell disease at higher risk of infection?

Sickle cell disease may cause damage to the spleen, kidneys, lungs and brain. Once damaged by sickled cells the spleen may not be able to filter bacteria from the blood as well as in other children.

As a result, infants and children with sickle cell disease have a compromised immune system. This means they are more likely to have certain infections which may be fatal.

Antibiotics to prevent secondary infections in infants & children with sickle cell disease:

National guidelines recommend newborns diagnosed with severe sickle cell disease (SS and S beta zero thalassemia) receive antibiotics by mouth twice a day until they are 5 years old.

Research shows that children with sickle cell anemia given twice daily penicillin (an antibiotic) had 84% less risk of

Streptococcus pneumoniae bacterial infection, which can cause serious conditions like pneumonia and meningitis.

Is there a treatment or cure for sickle cell disease?

Sickle cell disease is a chronic disease, meaning it does not go away. Early diagnosis and starting antibiotics shortly after birth for those with severe forms of sickle cell have greatly improved childhood survival.

Medications for sickle cell disease

The U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) has approved medications that can help prevent sickle cell complications in children. These include hydroxyurea (ideally started at 9 months of age) and L-glutamine (may start at 5 years of age).

Red blood cell transfusion

Transfusions are often required by children with sickle cell disease wither urgently for treatment of an acute complication or they may be given on a monthly schedule to prevent future complications. After 10 or more transfusions additional medication may be needed to manage iron overload that comes with this therapy.

Bone marrow/stem cell transplant

This treatment can cure sickle cell disease. It is a procedure that takes healthy cells from a suitably matched donor, most often a sibling. These are put into the bloodstream of the child with sickle cell disease, who has been prepared with chemotherapy. While only about 19% of patients have a matched sibling donor, sometimes less well matched related or unrelated donors may be used.

Cell-based gene therapies

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved

new therapies (exa-cel and lovo-cel) to treat sickle cell disease in people age 12 years and older—especially those who often have serious problems from sickle cell. The child’s stem cells are collected and repaired in the laboratory. Then, the child receives chemotherapy and the changed stem cells are given back to them. Learn more about sickle cell disease gene therapy from the

National Human Genome Research Institute.

Who are the doctors that care for children with sickle cell disease?

In addition to regular visits with their primary care provider, children with sickle cell disease should see a

pediatric hematologist regularly if at all possible.

More information

About Dr. Nuss

Rachelle Nuss, MD, FAAP, is a Professor at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and a member of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section Hematology and Oncology. Rachelle Nuss, MD, FAAP, is a Professor at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and a member of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section Hematology and Oncology.

|