By

Peter J. Taub, MD, FAAP, FACS

It is not unusual for a baby's head to look a little lopsided. Because the individual bones of a newborn's skull aren't yet fused together, pressure from resting in the same position can cause an infant's head to be misshapen. This may include a flattened area.

While an asymmetrical head shape is a common cause of concern for new parents, a baby's head typically rounds out after birth. Flat spots may also improve, especially with position changes and extra

tummy time during play. If the deformation is moderate or severe and not responding to position changes, helmet therapy may help.

Less commonly, an uneven head shape happens when the bones of the skull fuse together too soon. This rare condition, called craniosynostosis, may require surgery both to correct the head shape abnormality and in some cases to give the baby's brain room it needs to grow. It is estimated that about 1 in every 2,000 U.S. babies is born with craniosynostosis.

Baby's head: a brainy design

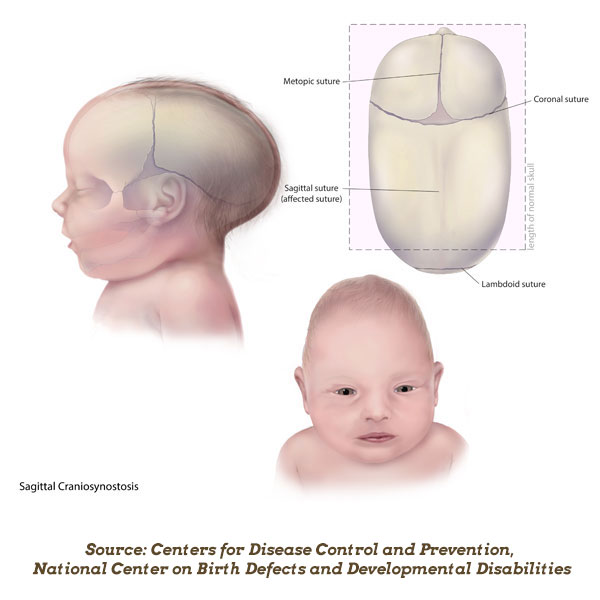

The soft, flexible spaces between a baby's six separate bones of the head, called "sutures," do more than help the head squeeze through the birth canal. They also allow the skull to expand rapidly during the first year of life, when the baby's brain more than doubles in size.

With craniosynostosis, two or more bones fuse together before a baby's brain growth is completed—sometimes even before birth. Depending on which of the sutures close early, and where they are located, the shape of the skull, brain and face can become distorted.

How is craniosynostosis diagnosed?

To help determine what's causing a baby's uneven head shape, pediatricians will talk with parents to piece together a developmental and family history. They will also conduct careful examinations, looking at the baby's head and face from several different angles as they search for raised or flattened areas and noting any asymmetry. This may be easier when the baby's hair is wet.

These observations and information will help differentiate positional plagiocephaly (caused by simple pressure in one area) from craniosynostosis (caused by bony fusion).

One sign a baby's uneven head shape was caused by position alone is the classic parallelogram shape. One side of the head may appear to be pushed forward, with the back of the head being flattened, the ear moved slightly forward, and the forehead pushed slightly forward on the same side compared with the opposite side.

Your doctor may gently place a finger in each ear and note the position of their fingers relative to each other as observed from above the baby's head. In the case of positional plagiocephaly, the two fingers will not line up opposite each other. Plagiocephaly is more common on the right side, and also shows up more often in male infants.

Types of craniosynostosis

Skull bone sutures that fused too soon may be felt as ridges that run along various parts of the baby's head. The baby's particular head shape will also point to the specific suture involved. Some of the more commonly seen types of head shapes, with the involved sutures, include:

Scaphocephaly: A long, narrow head is common with midline "sagittal" synostosis, when the suture extending from front to back over the top of the head fuses too soon. Sagittal synostosis is the most common form of craniosynostosis, accounting for about 40% to 45% of cases.

Scaphocephaly: A long, narrow head is common with midline "sagittal" synostosis, when the suture extending from front to back over the top of the head fuses too soon. Sagittal synostosis is the most common form of craniosynostosis, accounting for about 40% to 45% of cases.

Trigonocephaly: A forehead that is pinched on the sides with a ridge running from the bridge of the nose to the soft spot on top of the head signals a "metopic" synostosis.

Anterior Plagiocephaly: An asymmetric head and face with a flattened forehead, a raised eyebrow, and a deviated nose can result from "coronal" synostosis on one side.

Brachycephaly: A flatted and/or tall forehead, usually with pronounced flattening of the cheeks, a small upturned or "beaked" nose, and bulging eyes from "coronal" synostosis on both sides. This is often present in medical syndromes that involve the face and skull

Posterior Plagiocephaly: An asymmetric head with a pronounced ridge on the back of the head and a large bump behind the ear may result from "lambdoid" synostosis, which is the rarest form.

Surgery for craniosynostosis

Craniosynostosis usually requires surgery, both to correct the deformity and, in some cases, to avoid pressure inside the skull as the baby's brain grows. Extra tummy time and "molding" with a

helmet can correct

positional skull deformities; however, they are not, in themselves, effective in correcting craniosynostosis (although they are sometimes used after surgery).

Children with craniosynostosis are referred to specialists that include plastic craniofacial surgeons and pediatric neurosurgeons, and other experts who work as a team. These specialists are often able to make the correct diagnosis by examining your child but will arrange detailed imaging procedures, such as computed tomography (CT scans) ,before recommending surgery.

Depending how old the baby was when diagnosed with craniosynostosis and which suture is involved, different surgical options are available to either remove or release the fused bone. Additional reconstructive procedures may include placing springs or screws in the affected bones and "distraction" devices that slowly separate bone and let the healing process gradually fill it in.

Surgery for craniosynostosis should be performed in medical centers with experienced craniofacial teams and pediatric intensive care units. After surgery, children stay in the hospital one or more days and are monitored at follow-up doctor visits. Complications such as bleeding, infection and bone loss are relatively rare. Children who have these procedures usually grow and develop normally into adulthood.

More information

About Dr. Taub:

Peter J. Taub, MD, FAAP, FACS is a Professor of Surgery, Pediatrics and Neurosurgery at the Icahn School of Medicine and Kravis Children’s Hospital at Mount Sinai. He serves as Program Director in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery and is a former Chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Plastic Surgery and Past President of the American Association of Pediatric Plastic Surgery.

Peter J. Taub, MD, FAAP, FACS is a Professor of Surgery, Pediatrics and Neurosurgery at the Icahn School of Medicine and Kravis Children’s Hospital at Mount Sinai. He serves as Program Director in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery and is a former Chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Plastic Surgery and Past President of the American Association of Pediatric Plastic Surgery.